Watching two Michael Haneke features back-to-back doesn’t sound all that outrageous, right? What if they’re Funny Games (1997) and Funny Games (2007)? You start with one of the more disturbing flicks in Criterion’s closet, then immediately follow it with an American shot-for-shot remake that relives the same nightmare. My inner masochist couldn’t skip on tackling one of the stranger entries into Revenge of the Remakes, as two equally competent home invasion thrillers played out like a case of knife-twisting déjà vu.

Haneke jumped at the chance to make an American version of his Austrian commentary on the media’s exploitation of violence. Why wouldn’t he? A proud filmmaker saw an opportunity to help his bundle of anti-joy reach a wider audience, only made more relevant by the popularized 2000s period in horror history with “torture porn” leading the charge. Although, does shooting the exact storyboards like they’d been shipped overseas classify as a good remake? Haneke’s involvement is the trump card, because we’ve all seen what happens when a lesser filmmaker takes someone else’s script and creates something inferior (cough cough Cabin Fever cough cough).

The Approach

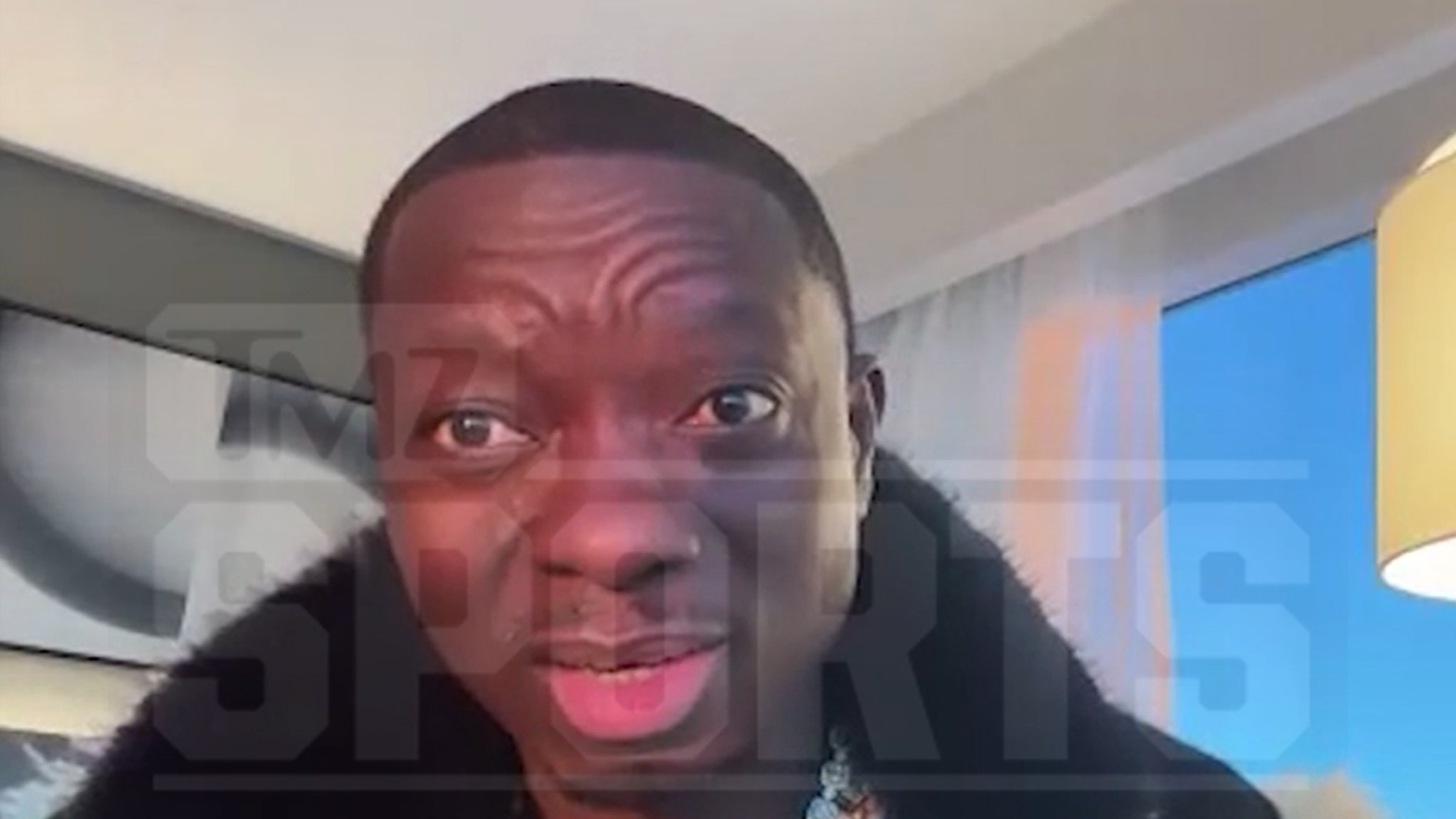

‘Funny Games’ (1997)

It’s the same. From the overhead highway opener to the closing hold on a deviant murderer staring back at the camera as a freeze frame. Avant-garde musical rebels Naked City get to hear their song “Bonehead” reused over the credits. There’s so little altered outside maybe how many pounds of steak are thawed (“three” versus “four,” curse our American greed)? Otherwise, Haneke doesn’t see any weakness in his wall-breaking narrative. Bless a filmmaker with the confidence not to question a single choice they once made, essentially insisting a movie so stupendous doesn’t require second guesses.

The queen of American horror remakes Naomi Watts and Tim Roth star as Ann and George Farber, doomed vacationers heading to their lake house with son Georgie (Devon Gearhart). Stepping in as the film’s vile torturers in snow-white collared shirts are Brady Corbet as Peter and Michael Pitt as Paul. If you’ve seen 1997’s original, you know what transpires because it’s copied and pasted like clip art. Peter and Paul ask the Farbers for eggs, their request turns out to be a ruse, and they spend the movie holding them hostage until a teased execution deadline. Before “Because you were home,” there was “Why not” — all we can do is voyeuristically watch as coincidental torment unfolds.

It’s a complex analysis because Funny Games goes against everything I believe about remakes. I’m always harping on filmmakers to find their voice while paying respect to someone else’s source material — but that’s not Haneke’s objective. It’s said that Funny Games (1997) might have been intended to be an English film from the start, then thwarted by budgetary issues. Funny Games (2007) allowed Haneke a second chance to see his first intentions become a reality, using the same blocking, frame selections, and props where possible. Haneke agrees that if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it — down to a hungry dog trying to raid an open refrigerator.

Does It Work?

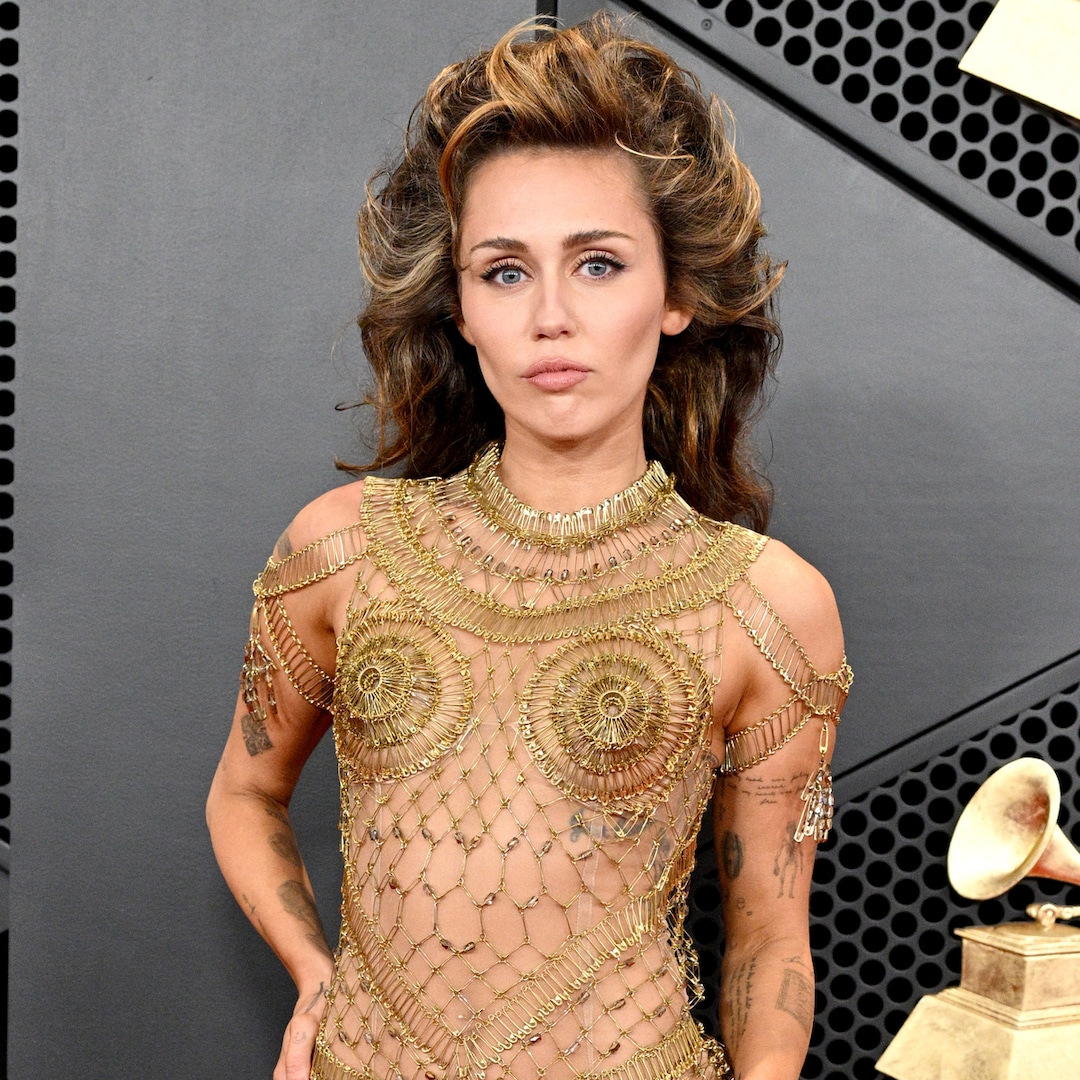

‘Funny Games’ (2007)

As an identical sibling film born a decade later? Yes, Funny Games (2007) is a well-acted psychopath’s getaway that generates all the same icky-awful feelings as Funny Games (1997). Haneke speaks directly to American audiences through Paul, keeping the metatextual commentaries about how we’re participants in the violence on screen. Everything about Funny Games (1997) works in Funny Games (2007) because Haneke chooses a path of meticulous replication. As a standalone, Funny Games (2007) successfully duplicates the agony, dismay, and delirium that stems from a movie that boasts its bleakness like a hole-in-one.

As a remake, Funny Games (2007) feels like a redundant experience for those who’ve already seen Hanake’s foreign-language shocker. There’s nothing to analyze beyond performances and dog breeds when watched in tandem, which becomes a question of tastes. Chances are, whichever you watch first will be your favorite because the following film will feel like cycling through repetitively morbid motions. Haneke cannibalizes his own market by trying to expand the story’s reach, which is still the right move considering how many Americans won’t “ruin” their movie experiences with subtitles.

Can you sense the conflict swirling in my head like a cyclone? Usually, I’d have all these comparison points about changes that either misrepresent or improve between sources and remakes — but Haneke does his damndest to leave no pebble out of place. Production took place mainly in Long Island, New York, which barely gives the “update” more of a wealthy American hideaway atmosphere. Still, besides some new driveway layouts and other minimal architectural differences, Haneke stays militant in his recreation. It works as an American version of an Austrian sensation that doesn’t skip a beat but feels needless if watched immediately after the original because there are no profound exploratory possibilities between either edition.

The Result

‘Funny Games’ (2007)

Funny Games (2007) is Haneke doing what he does best — again. Darius Khondji’s cinematography is merely crisper while reshooting the same angles with presumably better cameras (90s vs. 00s technology). It’s easier for English-language audiences to embrace a narrative without subtitles, but dialogue is nearly uttered word-for-word. Haneke avoids a situation like [REC] vs. Quarantine where Americanization fails the translation of international horror to stateside theaters, but possibly creates a new one that will frustrate fans of his first Funny Games ten years prior.

Performances from the English-language cast are the one aspect that helps set Haneke’s despicable exploitation apart and offer slim variations. Roth’s George isn’t a vocal screamer like Ulrich Mühe’s Georg Schober, bringing a broken quietness most appreciated after the whole sandwich-making distraction reveals its outcome. Watts matches Susanne Lothar’s Anna Schober, whether frustration or panic, paying homage to the original’s actress with chameleon abilities. Then there’s Corbet and Pitt finding more of a temperate threat level against original villain actors Arno Frisch and Frank Giering, likely to be welcomed into a residence due to their All-American appeal. Although, Pitt doesn’t play as coy when he talks into the camera during the fourth wall breaks, which has a fraction less fun with the twist — only super noticeable when compared side by side.

Neither is better. Both are successful as analytical presentations of violence to draw attention to our society’s sickest viewing habits. Both families endure the same unspeakable trauma, yet actors find borderline microscopic ways to make their performances their own. Haneke keeps the essence of his narrative pure in both versions, showing no desire to question his authority on the topic. The result is a rather impressive mimicry, for better and worse depending on your experience watching one Funny Games, or both, and how spaced apart you set your viewings.

The Lesson

‘Funny Games’ (2007)

I feel like I’m J.K. Simmons in Burn After Reading. “What did we learn here, Palmer? I don’t fuckin’ know either.” Month after month, I ramble on about how the best remakes manifest respectful reinvention. The point of a remake shouldn’t be to duplicate — and yet Haneke does just that for understandable reasons. Should more forgiveness be issued because the same filmmaker can cash in on an expanded market take that gives him access to new audiences? Again, “I don’t fuckin’ know either.” All I do know is Funny Games (2007) breaks my usual rules, and while it’s a worthless double-bill, isn’t wrong for its approach?

So what did we learn?

● Michael Haneke took full advantage of a situation few international filmmakers are given.

● Rules are meant to be broken every once in a blue moon, and Funny Games (2007) is a rare positive example of remake mimicry.

● Violent commentary against the media is unsettling in any language.

● You don’t have to teach an old dog new tricks.

Heed my warning and never watch both Funny Games movies in a row. It takes hardcore masochism to endure Funny Games (1997) and immediately chase that with the same nerve-shredding repugnance like you’ve just hit “Play Again.” There’s no reward for watching both, just a double-dip that’s oddly infuriating as the same events repeat in English. It’s the most curious experiment I’ve conducted here on Revenge of the Remakes (to date) because even the Cabin Fever ditto showcase a transparent quality dropoff. I’m baffled, annoyed, and enamored by Haneke’s ability to reshoot that same flippin’ movie, which I’ll never watch together again, but wholly defend as separate entities.

In Revenge of the Remakes, columnist Matt Donato takes us on a journey through the world of horror remakes. We all complain about Hollywood’s lack of originality whenever studios announce new remakes, reboots, and reimaginings, but the reality? Far more positive examples of refurbished classics and updated legacies exist than you’re willing to remember (or admit). The good, the bad, the unnecessary – Matt’s recounting them all.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/01/30/728/n/1922564/bae21b97679ba8cf1dcb88.10828921_.png)