Louis Posen launched a label on a dare. It was 1993 and he was directing a music video for Guttermouth when the band threw down the gauntlet, challenging him to put out a 7″ single. Posen cheerfully admits he had no business plan and zero funding. The guiding principle, he says, was “surround ourselves with good people, and we’ll be fine.”

More than fine, in fact: That label, Hopeless Records, has gone on to work with more than 200 artists — including Avenged Sevenfold, All Time Low, The Wonder Years, Taking Back Sunday and Yellowcard — that span from punk to ska, metal to emo. All told, the roster has sold more than 15 million albums. And now, Posen is celebrating the label’s 30th anniversary at A2IM’s Indie Week in New York (June 10-13), where he will receive the Lifetime Achievement Award Monday (June 10) at the organization’s 2024 Libera Awards.

While Posen’s decision to cannonball into the deep end of the label world might seem recklessly spur-of-the-moment, he now believes it was almost preordained. “We have all these moments in our lives that lead us to something,” he explains. One came in the fifth grade when a friend’s mom’s boyfriend took Posen and others to see the L.A. punk group X at the Reseda Country Club. “That was the first time I saw mohawks, stage diving, slam dancing,” Posen remembers. “And I was like, ‘Wow, this is unlike anything I’ve ever experienced before.’”

To celebrate Hopeless Records’ 30th anniversary, the label put together a traveling exhibit full of memorabilia commemorating key moments in its history. It will be open during Indie Week this week, before heading on to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland and the Punk Rock Museum in Las Vegas. Posen and Ian Harrison, the label’s GM, spoke about Hopeless Records’ origins, the challenges of condensing 30 years of activity into a single exhibit and the value of the independent sector.

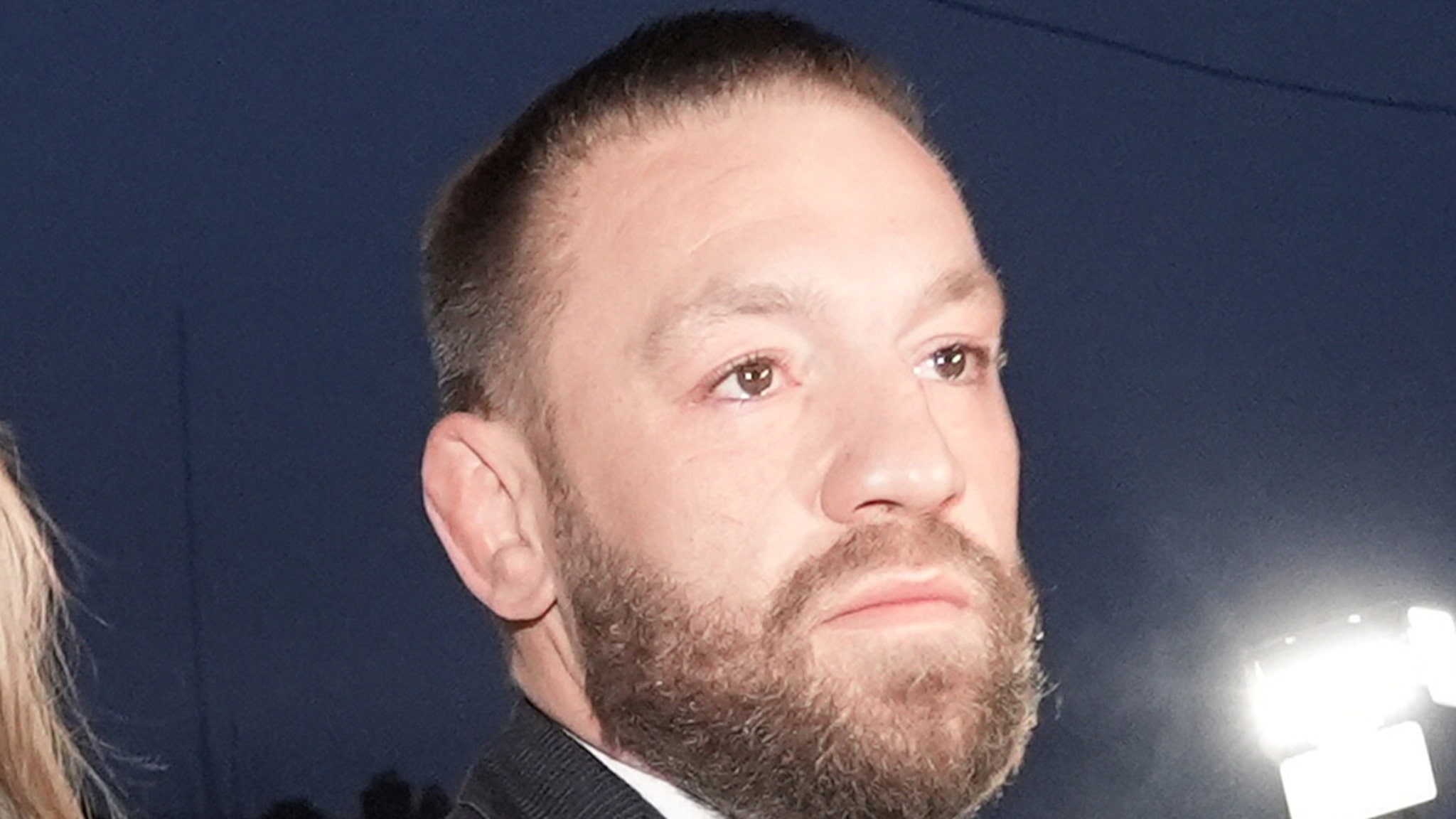

Hopeless Records

Courtesy Photo

What led you to start a label?

Posen: I was in film school at Cal State Northridge and I directed a music video for NOFX. The opener for the show we shot at was Guttermouth, who asked me to do a music video for them. And then while shooting that video, the band dared me to put out a 7″ record for them.

I went out and bought a book on how to run an independent record label. I tried to follow what it said, along with calling Fat Mike from NOFX because he had a record label. The first 7″ came out in December 1993, with the first song being called “Hopeless.” And that was where the name of the label was born.

I was still in college directing music videos at the time. It was really a one-off dare. Another group that I was doing a music video for was Schlong — a band with the drummer from Operation Ivy. While we were filming that video, the guys said, “Hey, we want to cover the whole West Side Story soundtrack and call it Punk Side Story. Would you put it out on this new label you started?” I said, “Let’s do it.” Things were so spontaneous back then.

What was the response to those early releases?

Posen: Guttermouth had a following. I was able to sell that first pressing of 500 or 1,000 records fairly quickly. The book also had distributors and their phone numbers so I called all of them. Some were willing to take the 7″, and then the rest I would sell at local Southern California retail stores. I would go drop them off on consignment and then come back a week later, see what sold and get paid.

The third release was all the music videos that I had directed along with videos from some of my friends who were directors. We put it on a VHS cassette and called that Cinema Beer-té, a play on “cinéma vérité.” After that, I decided to do the label full-time.

So you got the hang of things pretty quickly.

Posen: We’re still getting the hang of it; 30 years later, the best part about this industry is that it’s always changing and you always have to be learning. Those who feel like they know it usually get stuck and hit a ceiling. We need to be humble enough to learn from our successes, but more so learn from our mistakes and keep getting better every day. That’s been our philosophy and hopefully has been a part of why we’ve been able to survive for 30 years.

Hopeless Records

Courtesy Photo

How did you approach distilling three decades of history into a single exhibit?

Harrison: We’re pretty fortunate to have too much stuff — we could do two or three more exhibits if anyone was interested in that level of detail. We took a lot of inspiration from the Punk Rock Museum in Vegas, how they displayed the history of our world. We put our own tweaks on it.

We spent maybe two months going through stuff before we started building anything. And that was really just trying to get a sense of what we had, what we could get from artists, and what was important to tell the story. We have access to certain items that are interesting, but we also have big moments at the label that we want to make sure are represented, and sometimes those don’t always line up. It took maybe four months altogether. One thing we took away from this experience was feeling like we should do a better job archiving stuff in the future, both digitally and physically.

Posen: I always keep something next to my desk that reminds me of the beginning so I don’t forget where we came from. I kept the original Guttermouth 24-track two-inch tape in my office. Ian also spent some time — very kind of him — going through my garage with me to find all kinds of stuff that no one had looked at in 30 years.

The idea from the beginning was for it to be mobile, so we could go from museum to museum. Ian came up with the idea of putting these items in road cases, which was really cool because it has a music connection. You’ve got these music road cases like an artist would have on tour, but with the glass fronts like what you would see on the wall of a well-known museum.

How often did you have to ask artists for items?

Harrison: About 25% of the good stuff I’d say comes from artists. Avenged Sevenfold’s guitar that they used to record Waking the Fallen, that came from the producer actually who still had it. Neck Deep gave us a guitar. The Wonder Years gave us these two amazing lyric books with original song titles that had changed, early album plans, a pros and cons list about conversations with the label. That’s gold.

A lot of the good stuff came from artists, which is really nice and also requires us to have good relationships with them. That’s another bright spot for the label — we generally have pretty good relationships with these artists over time.

Posen: The third way we got stuff was becoming an expert at searching eBay, finding old T-shirts and things that we don’t have any stock of anymore. We used to put out these parody shirts that look like Rolling Rock, but they said “punk rock.” We found those on eBay.

Harrison: For maybe a month my house looked like a crazy person’s house. We just had the weirdest-looking packages coming every day. I bought a lot of posters that came in like these insane packages.

Hopeless Records

Courtesy Photo

Are there any items in the exhibit that are especially meaningful for you?

Harrison: For me, it would be The Greatest Generation workbook from around when The Wonder Years put out that album. That’s one of the top records in the company’s history. I remember us putting out that record and going through the whole process. To see the inner workings of that record as it was developing, to me that’s the coolest thing. And then I also threw in my own gold record from All Time Low when they first got a single plaque.

Posen: I mentioned we did the Punk Side Story that covered the whole West Side Story soundtrack. We actually got a letter from Leonard Bernstein‘s daughter — he’s the composer. She said, “This is an amazing version of my dad’s work and we’re not going to sue you.” It’s handwritten on her stationery. That’s an amazing piece.

And we have a letter from the late Senator Dianne Feinstein, who’s an icon in California, recognizing our charitable work with Sub City. Our belief that the artists’ voices can do more than make musicians rich and famous, that’s still the fabric and foundation of what we do every day.

What advice would you give to someone who aspires to start a label now and have it last 30 years?

Posen: I’m always hesitant to give advice because every individual is different. But there are definitely philosophies that I have that I like to share. We have a list of principles on the Hopeless site. If you’re just doing this for your own benefit, I think that’s not sustainable or rewarding over a long period of time. And it’s not about whatever the quick, easy path is. It’s about doing things the right way, treating people the right way. Those principles aren’t necessarily in fashion now, but we think those are universal and everlasting. And my biggest one is probably to still surround yourself with great people. This is really a team sport.

How do you feel about the health of the independent label landscape?

Posen: We’re a big believer that the independent music sector is an amazing place to build your career and create social mobility. This community does that. It’s an amazing environment to get started. Most independent labels don’t require you to have a Harvard degree, or any degree. It’s all about how hard you work — and how much you care. This community is what gave us the environment to start and thrive. And so we want to make sure this community stays strong and grows for the next generation of labels and other music businesses.

Ian made a list while he’s been putting this together — all of our albums that have reached 100,000 copies sold in the U.S. You only get a gold record at 500,000 or a platinum one at 1 million. We’ve got a few of those, which is awesome. But what’s actually more exciting is we have 33 albums that have hit over 100,000. To me, that symbolizes what we do and what independent music is all about. It’s not about superstars necessarily. It’s mostly about great music and art and allowing these artists to make a living doing what they do.

![Two Neighbors – The Summer (Official Music Video) [7clouds Release] Two Neighbors – The Summer (Official Music Video) [7clouds Release]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/IpUWOGlVPio/maxresdefault.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/11/07/930/n/1922564/a2d3a981672d2eff2fa4b3.27830525_.png)