Image Sources: Getty Images and Photo Illustration: Aly Lim

In her new book “Worn Out: How Our Clothes Cover Up Fashion’s Sins,” fashion journalist Alyssa Hardy digs into what the fashion industry actually looks like — from the perspectives of the people who are responsible for making our clothes. After a decade of working as a fashion journalist, Hardy realized that there were many stories going untold about the dismal conditions many garment workers face daily and the environmental degradation the fast-fashion industry is creating.

In this excerpt from “Worn Out,” Hardy brings light to the little-known-yet-pervasive culture of sexual harassment and assault at many clothing factories, both in the United States and across the world. As we pass the five-year anniversary of Hollywood’s #MeToo movement, Hardy proves that there are still many survivors’ voices that need to be heard.

Content warning: This article contains descriptions of sexual harassment and assault.

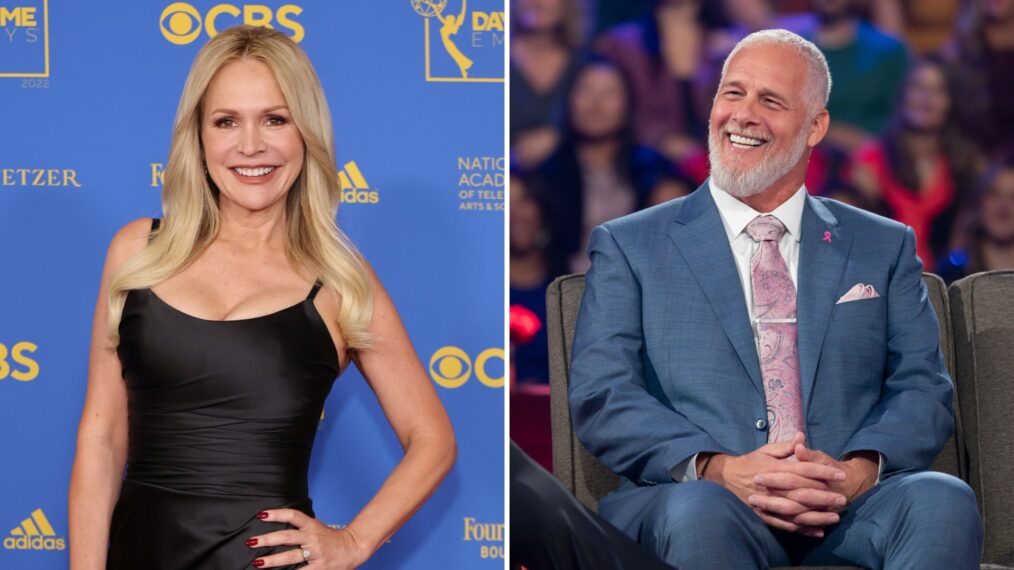

The world of fashion couldn’t keep #MeToo at bay for long — and celebrities certainly understood that fashion could tell a story loudly and clearly. In 2018, when the first Golden Globe Awards following the #MeToo explosion took place, some actresses resolved to raise awareness for Time’s Up, a new organization created to support victims of sexual harassment in the workplace.

I have covered red carpets as an editor for the past decade. At magazines like Teen Vogue and InStyle, where I worked, red carpets are our biggest night to direct traffic to the company’s website. It’s fashion, glamour, and ridiculousness all wrapped up in a five-hour special that audiences love to read about. My side of the evening is decidedly less spectacular, and usually involves me in my pajamas, hunched over a laptop with the television blaring in the background so I can hear people say which designer made which actress’s dress before I hit “publish” on my story. Usually, I’m writing anywhere from ten to fifteen stories a night, describing dresses in detail and trying to come up with silly headlines that include some sort of metaphor the rest of the editors and I will get a kick out of. A personal favorite of mine: calling Lili Reinhart’s high-low gown a “mullet dress.”

The night of the 2018 Globes, things were different. I was still in my pajamas, hunched over my computer, but we were no longer talking about clothing in the same way. There were no punchy headlines or labels to mention. The celebrities walked the carpet with serious expressions on their faces, ready to be asked about the movement. They all still wore designer dresses — Emilia Clarke wore Miu Miu, Nicole Kidman stunned in a Givenchy gown, and Dakota Johnson looked so incredible in a Gucci dress I could have fallen out of my chair when I saw it — but none of them wanted to talk about their outfits.

In an industry where most of the workforce is female, sexual harassment and abuse is rife throughout the factory floor, from the luxury business to fast fashion.

There were a few reasons for this. First, it was to show a sign of solidarity against harassment in the workplace and equal pay for women. Second, they were making the point that men get asked about their work and women are asked about their dresses. The two people who didn’t participate in the black dress protest that night stood out and made themselves tabloid fodder whether they meant to or not. A scene that would typically have been a sea of color, lace, glitter, and tulle was now devoid of it all. Just black dresses and suits that gave off a tone of seriousness and reverence.

It was a powerful moment for Hollywood and for fashion, but it stopped short of a true reckoning with how deeply the problem of gender-based violence and harassment impacts the entire industry, especially for the most vulnerable. The #MeToo and Time’s Up movement didn’t make it to the places where those beautiful black gowns and suits were made. I’m not suggesting the actresses shouldn’t have been there celebrating their own achievements — in a way, that would have been antithetical to the whole point — nor am I suggesting that they are responsible for abuse in other industries. Fashion could have been an entry point to talk about the marginalized people who were not reached by the movement. But instead, it was a well-intentioned but still performative act that missed a pervasive issue. In an industry where most of the workforce is female, sexual harassment and abuse is rife throughout the factory floor, from the luxury business to fast fashion.

When I first began researching this book, I exchanged texts with a woman in the Dominican Republic who wanted to tell her story of working in the fashion industry. She began working at age eighteen to help her mother support her siblings; her town was once known for being a denim capital, and brands like Levi’s subcontracted with several factories in her neighborhood.

For garment workers, silence is even more pervasive, because retaliation is not as simple as getting fired and then moving on to a new job.

When we agreed to speak, I thought she was going to give me information about the low wages and poor factory conditions, but instead she led with this: “Factory conditions were not very favorable, but it was the only thing we had here in Villa Altagracia. Many times the superiors wanted some women to have sex to get the job. They also prevented studying [for school].” It’s not that I didn’t expect all sorts of abuse to be taking place in garment factories, but I was learning just how bad it was for women. The gender-based discrimination that goes on in some of these places is not only about the lack of respect we give people turning the gears of fashion elsewhere, it’s often a life-threatening aspect of the work. The prevalence of assault and harassment is egregious, and it’s a direct result of how obtuse the industry can be about its own problems.

Another example came from a woman named Lorena, who I spoke to on the phone in 2020. She used to work in a factory just ten miles from where all of the celebrities were photographed protesting sexual assault on the Golden Globes carpet in Beverly Hills.

“I love clothes,” Lorena told me one evening after a day at work. She uttered these three words inside a raspy laugh. “I am fifty years old, but I don’t like to dress like I am. I dress casual.” Lorena is a garment worker who grew up in El Salvador and began working at a factory in her hometown when she was twenty-two years old, after her daughter’s father died. She had children and a mother to take care of and needed money. Jobs were hard to come by, but, “thank God,” she said, with a deep breath as she recalled her life back then, there was one at a factory. In the beginning, her job was to insert the tags that tell you the piece of clothing she was working on was “Made in El Salvador.” Although she worked from four in the morning until five or six at night, Lorena made less than a dollar for every grueling hour — not nearly enough to support her children.

“It was poverty,” she explained. Then, Lorena heard that in the United States, you could work in the garment factories and make more than what she was making in El Salvador. So she packed up her bags, left her family behind, and made her way to Los Angeles. When she got there, Lorena’s cousin took her to the factory where she worked and helped her get a job. Lorena was a trimmer at first, until she got her own sewing machine. She worked sixty hours and made $125 to $250 a week — about a fifth of the minimum wage in the city. Still, it was more than what she made in the factories in El Salvador, so she stayed and worked.

Lorena was matter-of-fact when she talked about her experience in the United States. She told me about the man who managed the factory where she was most recently employed. His name came out of her mouth sharp and cut like a knife. She said it again to make sure I heard it. “Noé,” she repeated, her voice lifting for clarity. “His name was Noé.” Noé harassed her daily. He would ask for dates, kisses, and sex in exchange for a break. A break that she needed after hours of difficult, taxing work on a sewing machine. Most days, Lorena never saw daylight.

He told her that if she wanted a “better job,” she knew how to get it: by sleeping with him. He would constantly ask her for sex, telling her that it would make her life at the factory easier. Often, she feared for her safety, but still she was able to dodge his inappropriate advances. Other coworkers at the factory were treated in the same way, and many of them weren’t able to walk away from Noé. They had to “give in,” she said. “To survive.”

“Noé,” Lorena said again, louder this time.

I realized that she was repeating his name because she wanted to make it clear that he no longer had power over her. Saying his name with conviction to a person she knows will put what he did in writing is her way of reclaiming what he took from the women at the factory. Noé would put his hand on Lorena’s ribs or back while she was working. Touching her inappropriately, not caring if she was uncomfortable. As she described this detail, there was an unnerving sobriety in her voice. There was no quiver or hesitation, just a resolve to tell her story. “I would tell him no, I would try to stop the advances, but, even then, whenever he would drop off my work at my station, he would touch me,” she said. “I would say, ‘You need to respect me!’ but it didn’t change things.”

Lorena spoke firmly about the abuse she endured at the factory throughout our entire conversation, but noted that she never told anyone at work what she was going through. Like the millions of women who kept these stories stashed away for fear of retribution before the #MeToo movement offered them new forms of protection, Lorena knew what would happen if she told on her boss. “Even if it was possible, I would lose my job,” Lorena reasoned when I asked her what would have happened if she had told someone. In her position, retaliation is not an unspoken threat; real threats of violence or removal were understood by everyone in garment factories. Losing a job that already pays you poverty wages would be devastating, and the managers won’t hesitate to kick you out on the spot.

The brands whose clothes she was making weren’t going to help either. “Only Noé checked our work. No one else ever came,” she explained. She didn’t even know what brands she was working for most of the time if she wasn’t able to see the labels. Often brands will claim transparency by listing the city, like Los Angeles, where the clothing is manufactured, but no representative from the company ever steps foot in the factory to see what’s going on. According to many of the workers I spoke to, representatives from the brands are led around by management, and they don’t speak to the workers. The real story is never heard.

When we spoke in April 2021, Lorena was still unemployed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. She had contracted the virus in early May 2020, and it put her out of work. She hadn’t paid her rent in months and subsisted on free food from neighborhood charities. Though she wanted to work again, she was hesitant about returning to a place where she may still be sexually harassed. The time away from her work allowed her the space to reassess some of the ways she had been treated by factory management. “I will not let anybody harass me and I will make sure that I’m treated with respect,” she declared. “And if I have to file a complaint for harassment, I will.”

She knew, though, that fighting back in garment factories can be incredibly dangerous. Just a week before our conversation, Jeyasre Kathiravel, a twenty-year-old woman in Tamil Nadu, India, was found murdered. Jeyasre was a garment worker who made clothing at Natchi Apparels, a supplier for H&M. Her male manager, who her family says had been harassing her for months, admitted to killing her and leaving her body on a farm near her parents’ house. The manager was only charged with murder, but Kathiravel’s parents say that she had been raped as well. “My daughter told me that she was being tortured at work,” her mother said following her death. She also explained that Jeyasre had attempted to report what was happening to her at work and nothing was done. What’s more is that according to the Tamil Nadu Textile and Common Labour Union, Jeyasre was not the only woman who was harassed by the managers at the factory.

Silence is a common response for most sexual assault victims, women and men equally, because promises of justice or restitution are so rare and often go unfulfilled. For garment workers, silence is even more pervasive, because retaliation is not as simple as getting fired and then moving on to a new job. Managers in some factories have been accused of threatening workers with serious physical and verbal abuse. In 2019, a complaint about a supervisor in a factory that made clothing for Vans and Nautica in Peenya, India, described a situation in which a worker tried to speak out about being sexually harassed and was chased and beaten by the staff. The report read: “The General Manager summoned her, abused her verbally and asked her to obey commands and never question any of the supervisors. He threatened her and took his boots off to beat her. The garment worker made a run for it and at the behest of the GM 20 men holding different supervisory roles in the factory chased her down and pulled apart her clothes and scratched her even as her colleagues came to her rescue.”

Following the assault, the police discovered that dozens of women at the factory had tried to report harassment and had been ignored. Many of the workers claimed that their supervisor had taken obscene photos of them, and some claimed he would watch pornography while at work. According to a worker who spoke with the press at the time, the women at the factory did report the harassment through a suggestion box, but found that their anonymous notes had been thrown out or ignored.

Factory garment workers are not treated as employees of the brands they are making clothing for and therefore don’t receive the same protection as someone who works at the parent corporation. After Jeyasre’s murder, H&M made a statement that they were investigating the matter, but such investigations typically happen only after someone has already been victimized. In 2018, Global Labor Justice published a report featuring interviews with more than five hundred women who were at “daily risk” of sexual harassment in factories in Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka that make clothing for H&M. In the aftermath, a spokesperson for H&M said they would review each level of their manufacturing to stop abuse before it happened. “All forms of abuse or harassment are against everything that H&M group stands for,” the spokesperson said at the time. Clearly, the company’s review did not prevent Jeyasre’s murder.

The response read like the typical refrain of corporations following a problematic headline-making incident. We don’t tolerate what happened [check!]. We’ll look into it ourselves and report back [check, check!]. For the most part it works: the public moves on from the story, and the brand gets to throw money at the problem and put their misdoings in the past. Unfortunately, for the people it matters to most, it always resurfaces. And that’s what happened with Jeyasre. Her manager was not a bad apple, this was a systemic issue.

Copyright © 2022 by Alyssa Hardy. This excerpt originally appeared in Worn Out: How Our Clothes Cover Up Fashion’s Sins, published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.

Read more stories about the five-year anniversary of #MeToo:

Image Source: Getty Images and Photo Illustration: Aly Lim

![The Penguin Showrunner Reveals Why Oz Killed [Spoiler] in the Finale The Penguin Showrunner Reveals Why Oz Killed [Spoiler] in the Finale](https://www.comingsoon.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2024/11/MixCollage-12-Nov-2024-09-58-AM-5921.jpg?resize=1200,630)

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/11/07/930/n/1922564/a2d3a981672d2eff2fa4b3.27830525_.png)

![Disney Meets Lovecraft in Lionsgate’s ‘The Little Mermaid’ Horror Movie [Exclusive Trailer] Disney Meets Lovecraft in Lionsgate’s ‘The Little Mermaid’ Horror Movie [Exclusive Trailer]](https://i0.wp.com/bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Screenshot-2024-11-12-102403.png?resize=1000%2C600&ssl=1)

:quality(85):upscale()/2023/09/28/687/n/1922564/754733d665159be5598c99.51953733_.jpg)