Spoilers ahead for episode 6 of The Last of Us.

Joel Miller needed to be indestructible; he also needed to die, often. There are more than 50 animations that can play when Joel, the protagonist of the 2013 PlayStation game The Last Of Us, passes from our earthly plane: His jaw is torn from his temples; his skin is singed to ash; blood spurts from the faucet of his throat as an infected zombie digs in for dinner. Seconds later, he appears again—alive, whole, healed, and ready to endure however many bullets it takes to secure the safety of his charge, the precocious (and immune) Ellie Williams.

This was always the central paradox of the Last of Us hero, helping to shape the game into not only one of the best PlayStation releases of all time, but—depending on whom you ask—one of the best stories ever told. It’s a point the critic Andrea Long Chu artfully made in a recent essay for Vulture: Players of the game watched Joel die so often that these deaths came to “define [players’] relationship to both Joel and the game as a whole.” And yet, in The Last of Us Part I, Joel canonically does not die. He lives long enough to finish his mission and secure Ellie’s survival. Chu argues, therefore, that Joel is bifurcated. There are not one but two Joels as experienced by players: one that’s “propelled to heroic heights” through his protection of Ellie, and another, weaker version with a “perilously high mortality rate.”

More From ELLE

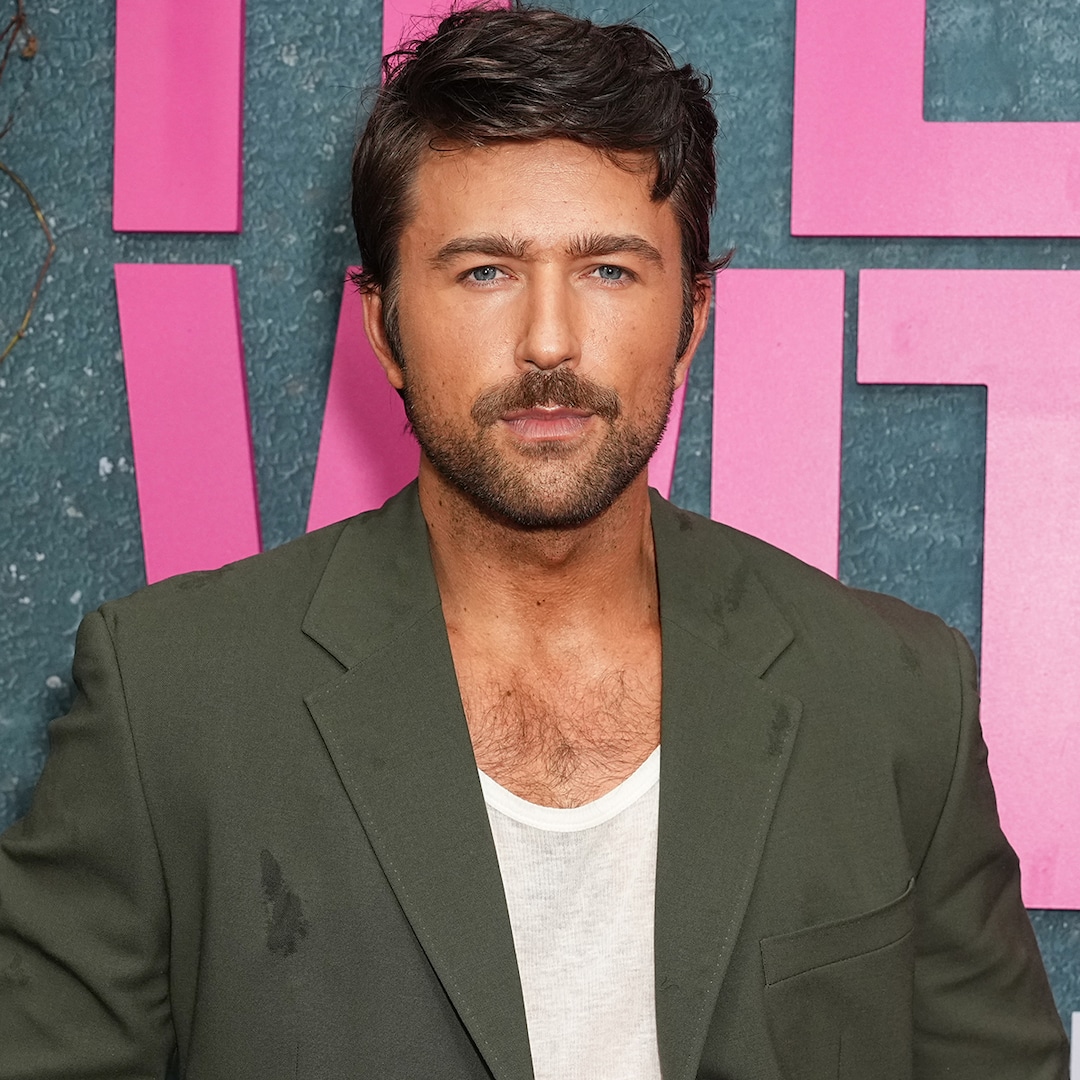

The now-hit HBO adaptation of The Last of Us, by necessity, needed to reconcile these versions. Through the avatar of Pedro Pascal, the regenerative Joel and the fallible Joel had to become one. The Joel of the TV show could not ever die—he has what some fans and critics refer to as “plot armor”—yet neither could he lose the desperation that drives him to make what is, ultimately, the story’s most controversial choice. The player’s desperation, and their repeated failures, needed to become his and his alone. An invincible man is not a desperate one. So Pascal’s Joel could never seem invincible, or even fully capable of healing.

Episode 6, the latest of the show’s nine-episode run, offers the finest example thus far of why removing Joel’s invulnerability was not only a necessary choice but a wise one. Up to this point, audiences had received a smattering of small examples of Joel’s declining state. He struggles to sleep and, when he can, mumbles through nightmares; he’s 56, with ailing knees; he’s hard of hearing in one ear thanks to years of firing off unmuffled gunshots. (In the game, we don’t get nearly as many reasons to suspect Joel’s past his prime.) But these inconveniences come to a head in episode 6, when Joel begins displaying the signs of panic attacks.

“Just a reminder, if you’re dead, I’m fucked,” a nervous Ellie (Bella Ramsey) informs him as the frame rate slows and Joel’s heart thumps to the rhythm of her voice. Immobilized, he leans against a fence post to right himself, blaming his temporary paralysis on the “cold air.” He’s just learned his brother, Tommy (Gabriel Luna), might be impossible to locate in the inhospitable Wyoming wilderness, and that’s only if the younger Miller has managed to keep himself alive. Joel doesn’t need Ellie’s pestering to remember what happens if he falls apart. Even his shoes are giving out on him.

His track record only worsens as the episode continues. At night, he sleeps through his watch and awakens, alarmed, to discover that his 14-year-old companion is the one guarding their camp with a rifle. Later, when Tommy’s crew surrounds them on horseback, a dog is tasked with sniffing out if the travelers are plagued. (Which, as we know, Ellie most certainly is.) The world blurs; the audio whines; Joel can’t so much as flex his fingers toward his gun. Fortunately for him, the pup can’t tell the difference between uninfected and infected-but-immune. Even so, Joel must live with the knowledge that, had the animal revealed Ellie’s condition, he would have been powerless to halt the resulting carnage.

Soon enough, Joel’s physical weaknesses make room for emotional ones. As he and Ellie are welcomed into the Jackson commune, he catches the first sight of his long-lost little brother. In the game, their reunion is affectionate but charged, the display of love between them muted by the burden of traumas past. Instead, in the show, they barrel into each other’s arms, their chuckles as astonished as the tears in their eyes. “I came here to save you,” Joel tells Tommy. The irony of his words is lost on neither of them, nor on Ellie, watching warily from a distance.

The rest of the brothers’ scenes are weighed by this transparency. Joel’s distrustful of Maria (Rutina Wesley), Tommy’s new wife, and of the Jackson community’s political make-up, which Tommy seems ashamed to call “communism.” (Remember, he’s a Bush-era military vet.) Joel disputes Ellie’s claim that they’ve been struggling on the road, apparently feeling insecure in the shadow of Tommy’s twinkling (literally, peep the string lights) new home.

When he and Tommy finally snag a moment alone, the episode throws another fighter into the ring with Joel. Tommy reveals Maria is pregnant, and when Joel reacts with less than the ideal amount of brotherly enthusiasm, Tommy whirls on him: “Just because life stopped for you doesn’t mean it has to stop for me.” Joel storms out, only to spot someone in the crowd of Jackson holiday revelers who looks like a grown-up version of his deceased daughter, Sarah. Once again, the camera tilts on its axis. Joel’s weathered lines crack open with hope, right until the moment the woman’s face is revealed, and he can no longer sustain the possibility that he might have actually saved Sarah. When the stranger strolls away, hand-in-hand with her own daughter, he’s forced to draw his coat tighter and carry on.

Tommy confronts him, a few scenes later, in the community workshop. There, he apologizes—“I know you’re happy for me; it’s just complicated for you. I’m sorry.”—and it’s as if such a display of humility tears away Joel’s remaining defenses. He reveals Ellie’s immunity, but more importantly, he confesses the extent of his own ineptitude.

In the game, Joel’s explanations for forcing Ellie on Tommy were always couched in deflection. “Tommy knows this area better.” “I trust him better than I trust myself.” None of them felt real, and Ellie tagged them, rightfully, as “bullshit.” But in the show, Joel’s not only so forthright it’s almost difficult to stomach, but Ellie overhears his entire soul-bearing monologue as well. First, he shares the story of the kid he and Ellie killed in Kansas City, and how Ellie saved his life in the process. “Five years ago, I would have destroyed him,” Joel tells Tommy. “But she had to shoot him to save me. Fourteen years old. Because I was too slow and too fucking deaf to hear him come.”

Still, perhaps the most jarring moment of the scene comes when Joel mentions his dreams. He can’t remember exactly what these dreams contain, only that “when I wake up, I’ve lost something. I’m failing in my sleep. It’s all I do. It’s all I’ve ever done—is fail her, again and again.” We needn’t question to which “her” he’s referring.

Joel pleads with Tommy to deliver Ellie to the University of Eastern Colorado, where the Fireflies were last spotted, because he “knows” he’ll get Ellie killed. Tommy is younger and stronger, and Tommy feels beholden to a “better future” for his own unborn child. Joel uses these (legitimate, if unfair) reasons to convince the future father to leave his family in Jackson.

Finally, we reach one of the most highly anticipated moments of the entire series. It’s the scene widely regarded as one of the best in video game history. Show co-creators Craig Mazin and Neil Druckmann replicate it with reverent fidelity, departing just enough to establish how the show’s Joel is different from the game’s.

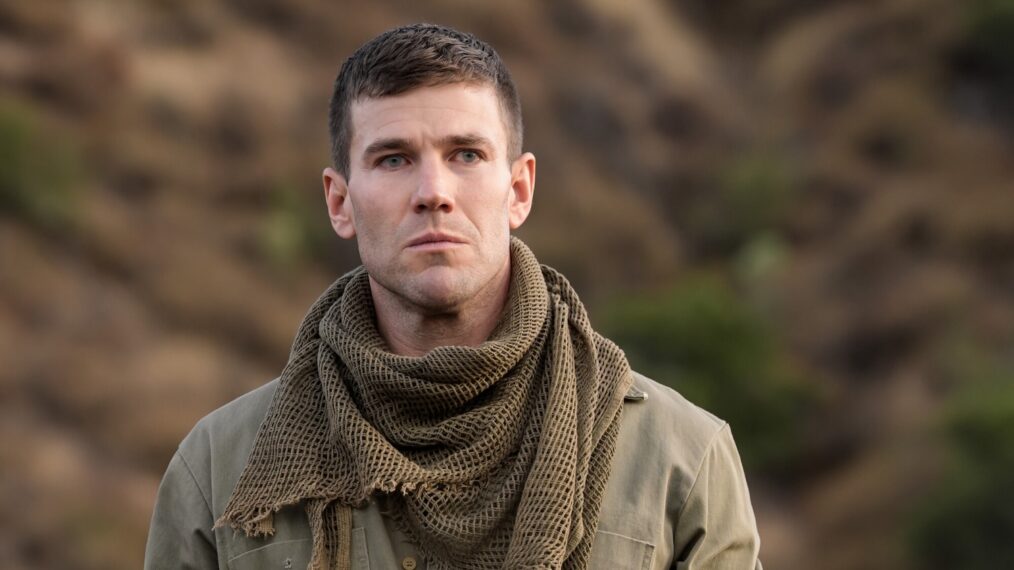

At this point in the story, the game’s Joel justifies abandoning Ellie because he can’t even acknowledge his fear: that he might lose her as he lost Sarah. The show’s Joel justifies abandoning her because the fear is all he can acknowledge. The difference is subtle, but in the context of performance, it signals a significant shift. Joel, as acted by Troy Baker in the game, is gruffer, fiercer, and more demonstrably violent. Even his argument with Ellie is loaded with barely restrained frustration. Pascal’s Joel is gentler, quieter, more obviously conflicted. Neither are incorrect depictions of Joel, and each work better in their respective mediums. One makes more sense for the Joel of the game—the Joel who, by necessity of gameplay, is really two Joels, one vulnerable and the other indestructible. The other makes more sense for the Joel of the show—the Joel who’s forced to try and be both.

It would be depressingly short-slighted to dismiss Pascal’s Joel as too soft. True, we do not see Baker’s Joel weep, or even confess the extent to which he’s frightened. But doing such does not make the Joel of the show weak. It makes him more transparent in his shortcomings, in a way that will become all the more essential as his journey with Ellie reaches its apex.

Near the end of the episode, after Pascal’s Joel has agreed to continue traveling with Ellie (and has softened to her even further), a bandit at the University of Eastern Colorado stabs him in the stomach. (In the game, Joel is instead impaled on a metal bar.) We know from trailers—and from the original PlayStation story—that he will not, in fact, perish. But the cliffhanger ending of episode 6 allows the audience the time to question what might happen if he did. What would it be like to witness the hero die, and not recover mere seconds later? Who might Ellie become without him? Some fans will already know the answer. But for those new to The Last of Us, the understanding begins to crystallize: Joel’s vulnerability might just be his most important attribute.

Culture Writer

Lauren Puckett-Pope is a staff culture writer at ELLE, where she primarily covers film, television and books. She was previously an associate editor at ELLE.

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/12/24/622/n/1922564/9eb50f2c676abd9f1647c5.05876809_.jpg)